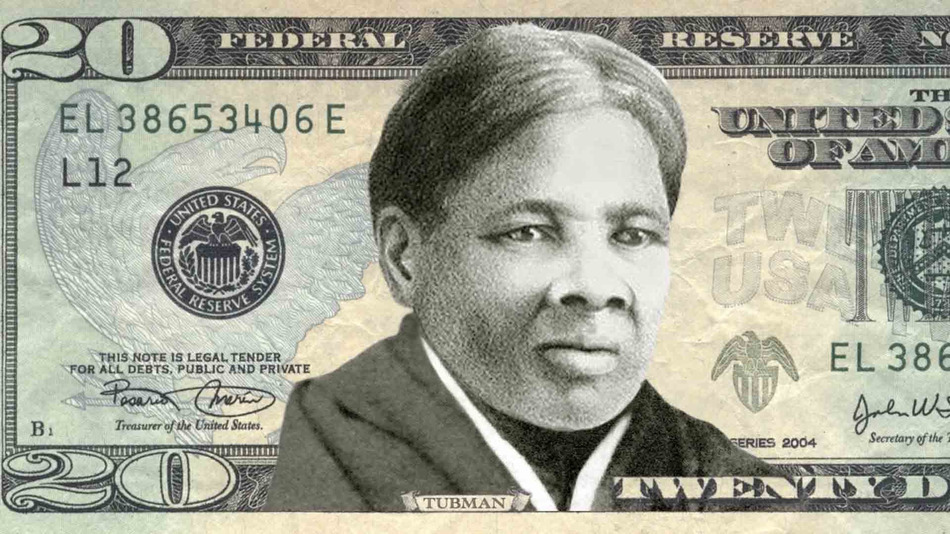

THE WomenOn20s CAMPAIGN scored a big victory on Wednesday, with Treasury Secretary Jack Lew’s announcement that Harriet Tubman would replace Andrew Jackson on the $20 bill. The decision to boot Jackson to the back of the note came after months of deliberation, much of which was centered around swapping out Founding Father Alexander Hamilton’s mug with a woman’s on the $10 bill. Although the consensus, by and large, is that the decision to cut the seventh president instead of the first treasury secretary is the right one, the fact remains that Hamilton should never have been on the chopping block.

Various media outlets have credited the success of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton with saving its subject’s placement on the $10 bill. The hit Broadway musical certainly may have scored Hamilton some points in the court of public opinion, but, in ethical terms, Jackson is — and has always been — the clear candidate for replacement.

Jackson held the presidency for two terms, from 1829 to 1837. For his heritage, politics, and military career, the Carolina native continues to be held in high regard by some Southerners and military servicepeople. He was born a poor orphan and died a rich former president. At least one historian believes Jackson’s campaign against the Bank of the United States echoes the anti-Wall Street sentiments of Senator Bernie Sanders (D-VT).

There’s no mincing words when it comes to Jackson’s career as a slaver, however. As the seventh president’s estate, the Hermitage, admits: “In all reality, slavery was the source of Andrew Jackson’s wealth.” As president, Jackson owned more than 100 slaves — a number that swelled to more than 150 by the time of his death in 1845. He was not a self-made man, but instead relied on slave labor to grow his own wealth.

He also advocated for “state’s rights,” a term bandied at the time — and, to some extent, today — as a dogwhistle to racists and plantation owners who opposed a federal ban on slavery. Although he did seek military power to enforce federal law in South Carolina — an action NPR’s Steve Inskeep credits with delaying the Civil War by 30 years — Jackson refused to do the same when Georgia stole “millions of acres of land that had been guaranteed to the Cherokee Indians under federal law.”

Which, of course, brings us to Jackson’s most notorious presidential legacy: the Native American genocide. More than a decade before he became president, Jackson led a military action against the Creek Indians, which cost them 22 million acres of land in what are now the states of Georgia and Alabama. A few years later, he negotiated treaties that cheated Southern tribes out of their land, which gave the federal government “control over three-quarters of Alabama and Florida, as well as parts of Georgia, Tennessee, Mississippi, Kentucky and North Carolina.”

Shortly after he became president, Jackson pushed his Indian Removal Act through Congress. A reiteration of the treaties Jackson negotiated in the 1810s, the Indian Removal Act required Native Americans living in the Eastern U.S. to trade their property for land in the West, or else become citizens of their so-called “home states.” Although billed as a peaceful and voluntary decision on the part of indigenous tribes and individuals, the Indian Removal Act resulted in a bloody and violent forced relocation, and, for the Cherokee, the Trail of Tears.

Clearly, Jackson should have been the first, and only, candidate for removal, because his legacy as a slaver and genocidal xenophobe should hold no honor in this country. He’s also the polar opposite of Hamilton, who was inexplicably the original target.

Like Jackson, Hamilton rose from humble beginnings to become one of the most powerful men in the U.S. He was a lifelong abolitionist, and co-founder of the New York Manumission Society: the state’s first abolitionist organization. Hamilton’s work as Secretary of the Treasury laid the foundation for the strong, centralized government that would eventually abolish slavery some 60 years after his death.

Additionally, as the country’s first treasury secretary, Hamilton deserves to be on our currency more than any other figure in U.S. history — with the exception, perhaps, of George Washington.

All this discussion of men should not discount the fact that Harriet Tubman — a black woman with disabilities, who was born into slavery and uneducated, led dozens of people to freedom, and later became the first woman in the States to plan and execute an armed military campaign, one which liberated more than 700 slaves in South Carolina — will become the first woman to appear on U.S. bills since the 1890s. Not only is she the first woman of color to grace our notes, but she is also the third woman of color — after Pocahontas and Sacagawea — to appear on any of this country’s money. And, of course, Tubman is the first African-American woman to hold a place on U.S. currency.

Jackson, deservedly, is rolling in his grave.