“I hope my book is a treasure — dog-eared, stained, borrowed, lost, torn. When people break up, I want them to argue over who’s getting custody of this book.”

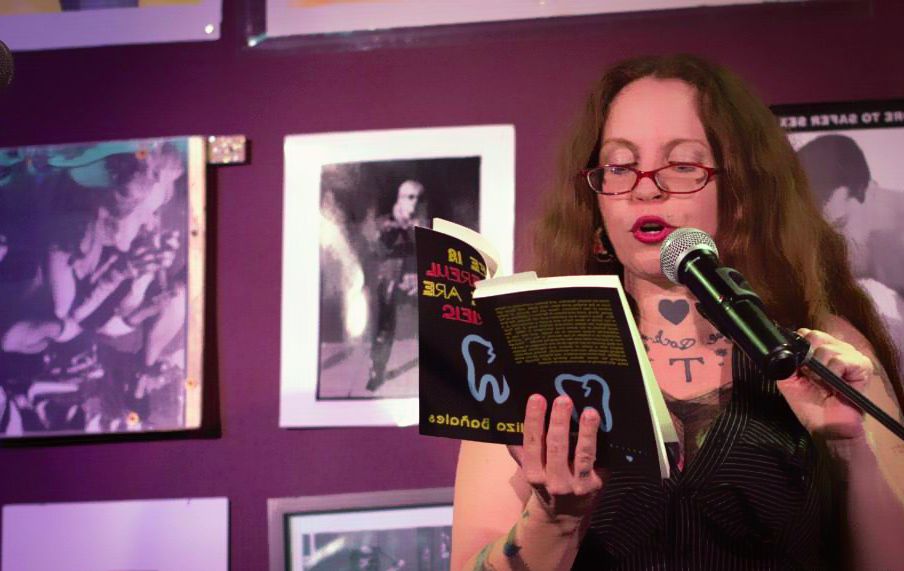

FOLLOWING IN THE FOOTSTEPS of powerhouse feminist activists-turned-scholars like Angela Davis, Cherrie Moraga, and Gloria E. Anzaldúa, Xicana performer and slam poet Meliza Bañales — aka Missy Fuego — finally took a mentor’s advice on “getting her sh*t on paper.”

This year, she published her first novel with LadyBox Books, following the life of her alter ego Missy Fuego.

A bad-ass with good intentions lost in a sea of existential crisis, the fictional Fuego is a heroine for the outcast in us all. Bañales sat down with LadyClever to discuss life after publication, her inspiration, and the “F-word.”

What inspired you to share these stories?

I was commissioned by Perverts Put Out, a reading series in San Francisco, to write a short story for the show they do every year at the Folsom Street Fair, one of the largest alternative lifestyle festivals.

“Anarchy,” which is a chapter in my book, started as a short story. But the more I worked on it, I realized I really wanted to write a narrative about Missy Fuego, kind of like how Charles Bukowski had [his alter ego] Henry Chinaski.

Most importantly though, when I started working with youth, I realized they needed and deserved a heroine in a story that was messy, funny, smart, and tragic — a huge wreck, but with ganas [desire]. I also realized that publishing a book as a woman of color was a radical act.

You really have to take it further than reading. Even with all those stories that are being talked about with punk and women and the ’90s and riot grrrl, there’s really no hero — it’s always: “This is what we did, and this is what happened, and here’s what ya’ll need to do now.”

So I just really wanted those youths to be like: “I’m f**king eighteen, and messy, and I’m beautiful, and there’s nothing wrong with me.”

You’ve been invited to teach at UC San Diego this fall, following the publication and success of your book. How does that feel?

It’s a serious pot of gold at the end of the rainbow! I’m teaching one class and I’m going to treat it like I’m never going to teach again. It’s an intercultural writing class called: “Outlaws and Outcasts: Writing in The Vein of a Rebel.” We’ll be looking at subcultures of outcasts: women of color writers, zines, small presses, experimental writing, erotica, slam and spoken-word, and renegade performance.

It’s unbelievable and it doesn’t happen to a lot of people bu,t once in a while, you write a book and it falls into someone’s hands, and then this blessing occurs.

How do you plan on balancing your revolutionary ethos with the constraints of academia?

I think to even get a degree is a revolutionary act. To get into an institution that doesn’t want us, that isn’t designed for us, and to be able to persevere and to keep holding space there [for ourselves] is an act of itself.

There are hardly any Women’s Studies classes. Xicano studies are losing money, and it’s mostly straight men [teaching them]. Theory in the university? They’re not teaching about any women.

That won’t be happening in my class — and it really took me understanding women-of-color feminists and the work that they do. The number-one thing that my students are going to remember is visibility. They’re going to remember that: “I have this professor who is openly queer, openly weird, and openly talking about these kinds of things.” It’s possible to be an outcast-weirdo and work in the academy, and I can’t wait to teach because I will be that voice that says: “You gotta move. You need to go somewhere. You don’t like college? Quit! The academy isn’t going anywhere, this is one thing you can come back and do later.”

In every “scene,” there seems to be some sort of exclusivity or out-group.You mention that during your riot grrrl days, you felt like an outcast. Although you’ve found your place in Xicana Feminism, do you think that label alienates other feminists? How would you avoid making anyone feel like that?

This is always asked by women of color, but it’s never asked of white feminists. It denotes that women of color feminism isn’t the standard.

The way I would avoid making others feel excluded is to try to make space for everyone’s experience, particularly trying to make space for myself first. I was always told: “You’re never gonna be happy being queer and you’re never gonna be safe or accepted.” This was enforced by American culture, but really enforced by Xicano culture. Then there’s the added baggage: “You’re already a woman, you’re already a Xicana Latina — and now you wanna be a gay? Do you have any idea how hard that’s gonna be?” So when I first heard there was such thing as Xicana Feminism, I felt like I had been cracked over the head!

I don’t think I’m exclusive. I felt that riot grrrl in the ’90s was exclusive, but I don’t think they set out to be that way. I felt like they were all in on some secret I wasn’t aware of, and those weren’t my priorities. I knew my priority was art, and the only thing that I can do is talk about myself in a context that is wide-open to interpretation.

So I’ve learned, just as Missy in the book learns, that exclusion is a concept you choose; Missy chooses to be the outcast — it’s not until she really experiences friendship that exclusion is a choice. You can feel excluded or you can show up and not be excluded. Just show up and we’ll meet halfway.

How much honesty is too much honesty? Do you ever battle with that concept?

It’s something I think about all the time, but I also believe — the same way Bukowski used to say — if you haven’t written anything that your parents don’t like or something the establishment doesn’t like, then you’re not really trying. Writing is not supposed to be safe. It’s supposed to be disruptive. I was nervous about putting out my book — there’s a lot of sex in there. There are a lot of things in there I haven’t talked about before. But I’m also aware that whatever you say, whatever you write, you f**king stand behind it. You piss someone off? Stand behind it. That’s why some writers come across as narcissistic and arrogant. They have to be — to get those ideas out there, the amount of work, it takes a lot of righteousness to be a writer. I don’t think people know how lonely or how maddening it can be, but that’s the cost of truth. You might be even more alone if you tell the truth, but that doesn’t mean I’m going to stop doing it!

Just remember… someone is [always] going to dislike you for being too honest — or not honest enough. But better to be too honest, because the people that really appreciate it will find you. The right people are finding this book. At the end of the day, this book was written for a specific person, and that’s an outcast.

Bañales lives in Los Angeles, and is a member of the Xicana feminist group Con Fuerza Collective, which is based in East LA. She is the author of Revolutionary Voices: A Multicultural Queer Youth Anthology, Without A Net: The Female Experience of Growing-Up Working-Class, Baby Remember My Name: New Queer Girl Writing, and Word Warriors.

Get your copy of Life Is Wonderful, People Are Terrific, Meliza Bañales’ book chronicling the adventures of Missy Fuego, here.

Cover/featured image credit: Evan Emerson

-300x169.jpg)