MOST PEOPLE IN THE U.S. have never heard of a medical procedure called symphysiotomy. In recent years, awareness has been thrust upon the consciousness of the Irish people and government by the work of activist group Survivors of Symphysiotomy. The procedure, first developed in the 1800s but performed throughout the second half of the 20th century in mostly private Catholic hospitals across Ireland, involves sawing women’s pubic bones apart to widen the birth canal, encouraging vaginal birth and the ability to bear an unlimited number of children (though the latter was hardly a result). Records show the procedure being performed as recently as 2005.

MOST PEOPLE IN THE U.S. have never heard of a medical procedure called symphysiotomy. In recent years, awareness has been thrust upon the consciousness of the Irish people and government by the work of activist group Survivors of Symphysiotomy. The procedure, first developed in the 1800s but performed throughout the second half of the 20th century in mostly private Catholic hospitals across Ireland, involves sawing women’s pubic bones apart to widen the birth canal, encouraging vaginal birth and the ability to bear an unlimited number of children (though the latter was hardly a result). Records show the procedure being performed as recently as 2005.

Ireland is the only developed country in which this procedure was still performed well into the 1900s. Symphysiotomy is much more dangerous than a C-section, with higher rates of injury sustained by both the mother and the baby. Some infants died or sustained brain damage due to the procedure, and survivors who have been subjected to procedure have suffered decades of pain, disability, and incontinence as a result.

At least 1,500 symphysiotomies were performed in Ireland in the second half of the 20th century. Some of these procedures were performed after a woman delivered by emergency C-section, in order to prevent the need for a C-section in the future; some received the procedure while in labor, and others received it as a “prophylactic” measure against the need for a C-section before going into labor. Today, around 400 women on the receiving end of the procedure survive. There are likely more, but some women aren’t even aware they were subjected to the operation – oftentimes, it was performed without acquiring consent and without the patient being informed of it. The suffering of these women has not been redressed in the form of compensation or an official acknowledgment of wrongdoing on the part of the medical establishment or the government that did nothing to stop it.

But as survivors began organizing and raising their voices, it became difficult for the Irish government to continue turning a blind eye to the dark history of symphysiotomy and the toll it has taken on survivors’ lives. In 2014, the government developed a “redress scheme” to provide compensation to survivors for their suffering. Monetary awards ranging from 50,000 to 150,000 euros were offered for some 50 years of disability, depending on the particular type of symphysiotomy the applicant underwent (post-C-section being deemed the most severe form of the procedure).

There were numerous problems with the redress scheme, however. On the technical end, the deadline for application was extremely short, and many women could not obtain medical records in time to provide the required paper trail for their procedure and its consequences – many of these records have been “lost,” or hospitals charge a fee for them that women can’t afford to pay.

The Survivors of Symphysiotomy (SoS) have emphasized a major shortcoming of the redress scheme on the moral end: taking a settlement according to the scheme, if such is offered, comes with an “ex gratia” clause, meaning no fault is admitted by or placed on the government, the medical institution, or particular medical professionals. Marie O’Connor, chairperson of SoS, told TheJournal.ie: “For many people it’s more important than compensation – truth is more important than anything else.” The redress scheme fails to acknowledge that a grave wrongdoing was committed against these women, and that medical practitioners along with the state are culpable.

Those who refused to take a settlement based on the parameters of the scheme, and those who were offered no such settlement, risk winning or losing all in court. Over the past few years, three cases have been brought before the High Court with varying results. In 2012, Olivia Kearney, who received the procedure after a C-section birth, won her case and was awarded 325,000 euros. This represented the first public acknowledgment of wrongdoing by the government. In 2015, two more women brought their cases to the High Court. One survivor whose symphysiotomy was administered after a C-section birth won her case and was awarded an undisclosed settlement this February. On May 1st, the court ruled against a woman whose procedure was administered 12 days prior to childbirth; this does not bode well for future cases for women who received the procedure as a preventative measure against C-section.

The legal system is one apparatus for seeking justice for the survivors of symphysiotomy, albeit a shaky and unreliable tool for many of these women. But it’s not the only method activists are employing for recognizing and addressing the trauma these women have suffered. Second-generation Irish-American artist Mairead Delaney has been working with the SoS for the past two years, learning their stories and developing ways to convey them through art. She is pursuing her MFA in Studio Arts from Burren College of Art in Ireland. Her undergraduate work at Marlboro College in Vermont focused on the political, religious, and moral underpinnings of symphysiotomy and the communication of private trauma through visual art.

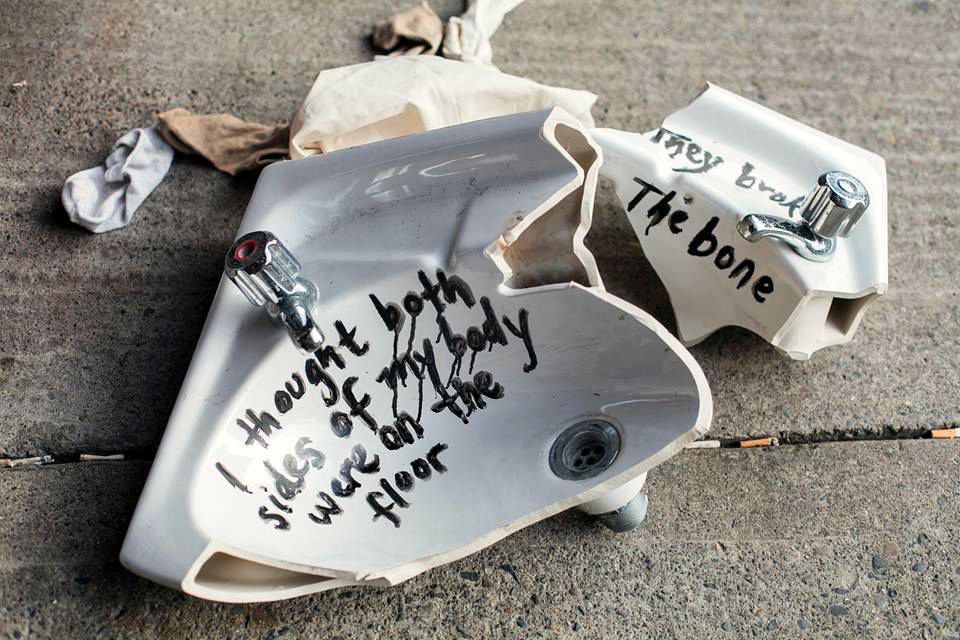

Mairead’s graduate work has been focused on transposing the themes of her earlier work into performance art. Over the past few months, she’s performed a series of public pieces at the gates of the National Maternity Hospital in solidarity with the women fighting the most recent court cases; the title of her series, “Hold Harmless,” is based on the redress scheme’s ex gratia clause requiring the women to hold the government and medical establishment harmless for their suffering. She responded to our questions regarding the “logic” underlying the procedure as well as the role of art in processing and communicating trauma.

How did you come to learn about symphysiotomy?

I came to Ireland in the summer of 2013 to research the institutional abuse of women in the Magdalene Laundries. That August, the Irish Times reported on Survivors of Symphysiotomy’s response to the proposed redress scheme, similar to the one provided for the Magdalenes. I was familiar with the practice of symphysiotomy in Ireland, but only as an antiquated procedure, not as something that exists in living memory and in living bodies. The youngest survivor is 49.

I was deeply struck by resonances with personal experience with medical violence. I contacted Marie O’Connor and we arranged a meeting, which marked the beginning of a cooperative relationship. I returned on an artist residency in January 2014, during which I traveled the country to meet and speak with survivors about their experiences. Their portraits and voices became part of my undergrad thesis show. As the urgency around these cases increased, I felt I needed to return to continue the work, and have been living in Ireland and collaborating with the collective since September.