She’d often shout at the TV. But she never watched sports. And the only bets she placed were on the inevitable errors of others. Her grammar books were her bookies.

“You mean my brother and I,” my mother would pontificate from the kitchen, amid the cleaning clanging of the night’s dinner plates and pots. “Not my brother and me! Me did not go to the party,” she’d exasperate. (Unless, of course, “me” is Cookie “Me the Robert Downey Jr. of Cookies” Monster.) See, in our house, my mom was pope, bishop, and priest, you name it, lording over Ps and Qs, dotted Is and crossed Ts. Punishment for blunder: 50 tongue-lashings.

“It’s become so prevalent to use the objective as the subject of a sentence,” she’d say, “Really awful!” And my sisters and I would scoff, because, who cared?

What the above means is as follows: “He and I” are subjective. “Him and me” are objective. When the subject is singular people usually get it right and say “I took her,” not “Me took she (or her).” But when two people get involved in the same sentence, non-grammarians always seem to say, “Him and I took…” (instead of “He and I”), or “Me and Jenny went …” (instead of “Jenny and I went.”) Fun stuff.

In my house there was no slang, no curse words, and we always, always had to use proper names for body parts and its ablutions– so much so that for the longest time (before I could spell) I thought I was asking to take a beam.

Her insistence felt like mountains made from mole hills, but she was always right– still is– and as such she’d climb to the alp’s top and stick her purist’s flag in its summit.

It didn’t matter what we watched, there was always something to correct, her voice like a teacher’s red pen pointing flaws in a paper and shredding paragraphs to pieces with quick cursive scribbles in the margins of continuous printer paper. You know, the kind that was transparent as a nightie, and where you had to gently tear the serrated edge.

You might think that her persistence would have encouraged my sisters and me to be more cautious, but we’d roll our eyes and turn the volume up a notch higher on Dawson’s Creek. I mean, talk about literate kids. Who needed mom? (Although, I still have to spell check any of the “rrheas:” dia, gono, and galacto.)

Mom believed that people should know how to use language correctly. Break the rules of grammar purposefully and artfully, sure, but not stupidly. English, she encouraged, is a subtle and nuanced language, much more than people realize, and more so than most other languages.

Butchered grammar can drown out even the best speech. It can remove you from the experience.

It’s like swearing–and while like most, I enjoy a well-placed, perfectly intoned f-bomb– I am not unwilling to admit that when every other word is a dirty one, those words lose their ability to punctuate and accentuate. Bad grammar does that too.

“One of the reasons I like British TV better than American TV,” my mother once said, “is the way words are used. The British aren’t afraid to sound smart, even with a Yorkshire accent.”

As for television, we were only allowed 30 minutes a night, and without a doubt, mom would chime in somewhere around minute 23 and ruin it all. For as limited as our TV was, it was supposed to be an escape, not another English lesson.

All she could hear were the errors.

****

Last June, The Writers Guild of America (WGA) released a list of the 101 best written TV series. The list spanned 7 decades and featured some of the most beloved shows from television’s past, like M*A*S*H and The Mary Tyler Moore Show.

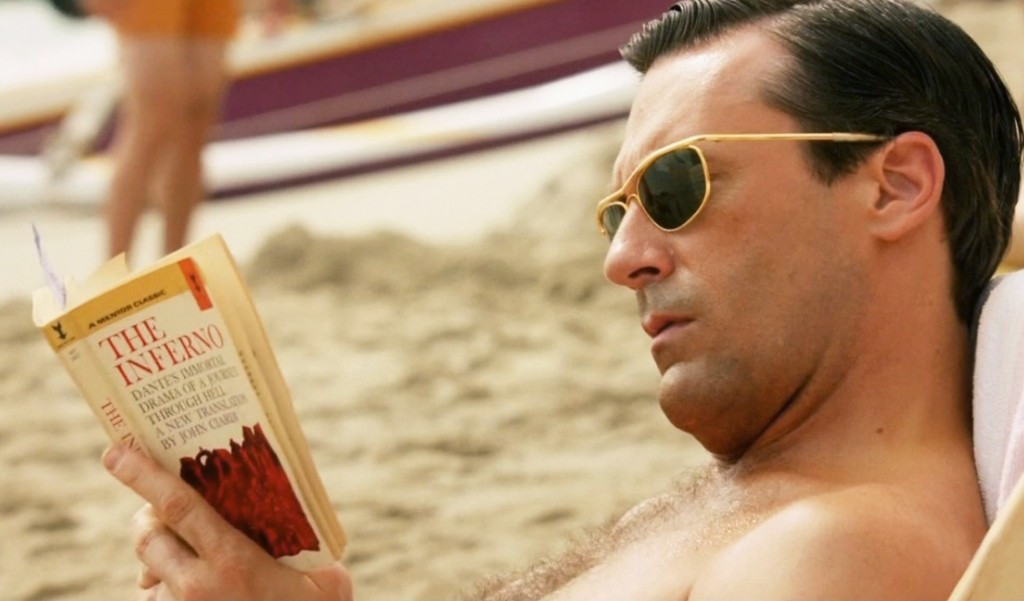

Coming in at lucky number 7 was Mad Men, the AMC drama that’s considered by audiences and critics alike to be one of the best written TV shows. Ever. The only other contemporary shows that beat Mad Men were Seinfeld and The Sopranos.

As Mad Men draws to the end of its 7th and final season, it felt natural to return to its beginnings– see how and where it all began and shake hands once more with the Sterling Cooper camp during their formative years.

Don Draper has come a long way from his first meetings with Rachel Menken and his “I’m not going to let a woman talk to me like this,” attitude (though he’s still a philandering alcoholic), and likewise the whole Sterling, Cooper, Draper, Price, Olsen, Harris (née Holloway), Campbell cavalry have matured, though certainly not without serious fumbles and foibles of their own. It’s still to be seen who, if anyone, will make it safely to the end zone.

Still, throughout the show’s run, the audience allowed Mad Men its dalliances and drinking binges, in part inveigled by Don Draper and his merry crew, but perhaps more so, by the perfectly reproduced world that show runner and creator Matthew Weiner constructed. It is nearly period-perfect.

Weiner’s dogged attention to detail, his exalted and obsessive vision has been well-documented. Mad Men is not, and was never, slap-dashed together the way Hollywood churns out box-office bombs or the way the Internet produces content. Its approach to detail spits in the face of modernity, and is necessary for creating meaningful work. It is carefully, if not obsessively researched, and executed flawlessly; just as you might expect an ad to be, or as you hope the content you read is. It is a show that slowed everything down—even the pacing—to make painstakingly sure that everything was right, especially in the face of all its characters wrongs.

Matthew Weiner’s nitty-grittiness inspired much reverence, and did what good art is supposed to do: he made people want to be better. Even Breaking Bad creator Vince Gilligan once remarked, “Now I always weigh the meth on the show to the 100th of a gram.”

Its anachronisms are few– Weiner has copped to two– and many are up for debate, including the glaring “mistake” that ad executives from that era have pointed out: not only was the term “Mad Men” not coined by the ad execs of Madison Ave., the term itself was not around in the ’50s. In fact, have we ever once heard the term used on the show?

For his part Weiner has enjoyed the microscope, saying, “I’m glad that we’re held to a high standard, and I’m glad that people get pleasure from picking it apart.”

However, anachronisms aside, there is a much larger, much more problematic error that frames the entire series. One that quite frankly would not have made it past Peggy Olson on her first day as Don’s secretary.

I’ve remarked on typos before, and have often come to the point of: so what? The same feeling I had when I was younger. But when so few people have done it better than Matthew Weiner, it’s heartbreaking to see all of the eggs I placed in his basket coming crashing down, Humpty Dumpty style.

If you don’t catch it at first, you’re not alone—the error must have slipped past countless eyes. But that one little, unassuming apostrophe shouldn’t be there, and like a sentence with too many swear words, it’s all I can see now; it’s all I hear.

At first I thought there had to be a reason. Were possessive and plural rules somehow different in the ’50s, or in the 1960s, the year Mad Men begins?

Alas, no.

In 1960, while Sterling Cooper and Madison Avenue may have given its twenty-something men license to drink, smoke and harass women, it definitely didn’t allow them the freedom to make copy errors. “1950’s” in this sentence, would not have passed muster.

The job of someone like copy writer turned copy chief, Peggy Olson, was to think things through and ask the most detail oriented questions: the annoying, seemingly trite kind my mother finds joy in.

Where does this leave us? Maybe as Season 1, Episode 1’s title suggests, smoke got in the eyes of whoever wrote it. Or maybe, as I so desperately want to believe, it’s Weiner’s ironic critique– an elegy of sorts to copy editors, that nearly extinct breed.

Or maybe, worst of all, this is just a mistake, a carryover from the current “post it now, fix it later” generation. Because while Mad Men is a show about truth, and other gray areas, there is no gray area here. They got it wrong from beginning.

It only took us 7 seasons to find out.

Is it possible to be so upset about one apostrophe? Yes. All it takes is one quick peek into my past to understand why. When I found myself yelling at the screen of my iPad, I realized (as most women do), I am becoming my mother.

It only took me thirty years to realize.

-300x200.jpeg)

-300x241.jpeg)