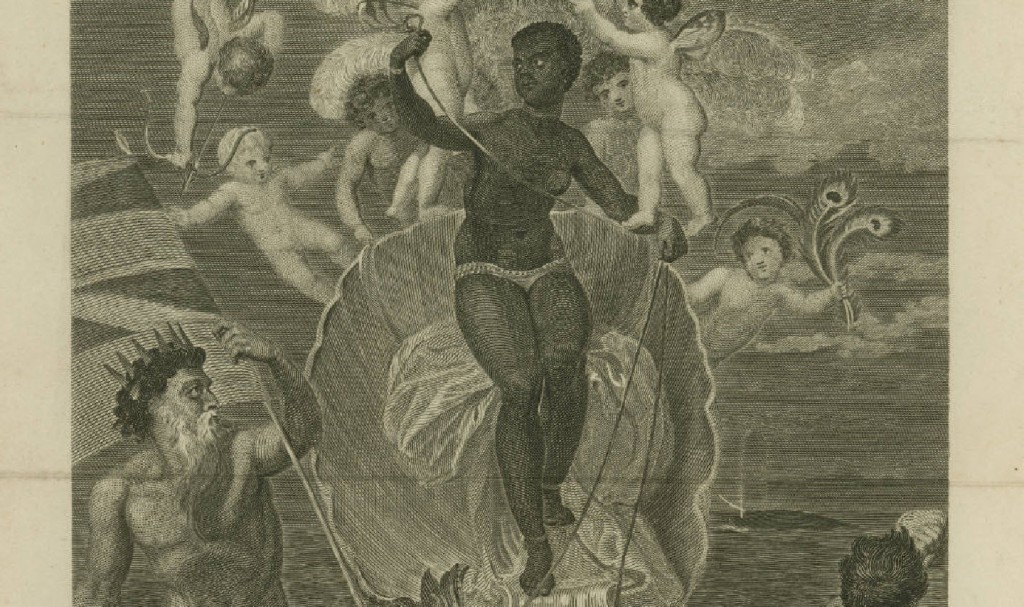

“The Voyage of the Sable Venus from Angola to the West Indies,” by Thomas Stothard, Esquire, which inspired the title of Lewis’ book

MOST PEOPLE EXPERIENCE POEMS as so puzzling and irrelevant that new books of poetry are burdened with the task of proving their right to exist. Authors address this anxiety with ultra-relevant topics — especially the Internet — or using aggressively un- or anti-poetic language, so that their poetry hardly resembles poetry at all. Some books, however, are so vital, that they transcend the question of poetry entirely. Voyage of the Sable Venus is such a book, if there ever was one. Although it’s her first, Robin Coste Lewis has nothing to prove: her language is crushingly sublime. It’s the kind of verse that makes you pause, breathless, to think or just feel — but not for too long, because the only way to breathe again is to read on.

The title refers to the conceptual project that takes up the bulk of the book, in which Lewis creates poems out of the titles and descriptions of art works featuring black women. The significance of this project, and of its undeniable success, takes a little “poemsplaining”: there has been powerful outcry from contemporary poets of color (esp. The Mongrel Collective Against Gringpo) about the heartless white supremacy inherent in conceptual poetry. Case in point: Kenneth Goldsmith’s “conceptual poem” made up of the autopsy report of Michael Brown, famously ending on a description of his genitals. The triumph of Lewis’ conceptual poetry — it won the National Book Award in Poetry for 2015, the most prestigious prize for poetry in America other than the Pulitzer, and is on pretty much every “Best of 2015” list — puts “gringpo,” as the Mongrel Collective has dubbed it, to utter shame while reclaiming the techniques of conceptual poetry for those who deserve it.

This project is sandwiched by sections of Lewis’ lyrical verse, which, far from acting as padding, establish her voice and add a level of accountability to her project. Conceptual poetry tends to hold the reader away from the writer, since we are deprived of her words. Lewis pre-empts this issue by letting us in right away, establishing the issues with the first poem “Plantation”:

Because you had never been hungry, I knew

I could tell you the black side

of my family owned slaves

and then letting us deep into her heart and mind with the incredible “On the Road to Sri Bhuvaneshwari”:

His capitalist glance mirrors our Orientalist tans.

You’re lying, I say. Save it

for somebody pale. He smiles, passes

me a bidi. I’m bleeding, but lie

So I can go inside and see

that burnt, charred piece

of the Goddess that fell off

right here.

Conceptual poets, bizarrely, often seem to think that by escaping their own words, they can escape feeling. Why that is a worthwhile goal is hard to say, but it does seem to get you invited to the White House. Instead, Lewis shows us that other people’s words are rife with feeling — mostly suffering, but also love, glory, hope, and curiosity. Instead of evacuating pre-existing words of sense, Lewis evacuates them of their senselessness, organizing them both by year and by ear. “Voyage of the Sable Venus” (and here I mean the section) is the most perfect embodiment I’ve ever seen of Saidiyah Hartman’s theory of redress, from her book Scenes of Subjection, which she describes as “an exercise of agency directed towards the release of the pained body, the reconstitution of violated natality, and the remembrance of breach.” Lewis achieves redress for the black female subject within both art history and conceptual poetry.

Conceptual poets, bizarrely, often seem to think that by escaping their own words, they can escape feeling. Why that is a worthwhile goal is hard to say, but it does seem to get you invited to the White House. Instead, Lewis shows us that other people’s words are rife with feeling — mostly suffering, but also love, glory, hope, and curiosity. Instead of evacuating pre-existing words of sense, Lewis evacuates them of their senselessness, organizing them both by year and by ear. “Voyage of the Sable Venus” (and here I mean the section) is the most perfect embodiment I’ve ever seen of Saidiyah Hartman’s theory of redress, from her book Scenes of Subjection, which she describes as “an exercise of agency directed towards the release of the pained body, the reconstitution of violated natality, and the remembrance of breach.” Lewis achieves redress for the black female subject within both art history and conceptual poetry.

Some highlights of the middle section, for me, were “VII. The Queen Has Her Hair Done”:

Cleopatra holding a—?

Cornucopia Attendants moving

from left to right linen,

from mummy-wrapping Aphro

Dite rising from the bath

and “XXII: A Refusal of Time/Her Absence Filled the Void”:

D-Man in the water, Pomo-Afro-Homo Peacock

of the Sea, the Spirit of the Dead, watches the Message

These two poems stand alone, but overall, “Voyage” is of a piece. The impact comes from accumulation and repetition, just like systematic oppression. The question “Voyage” asks, then, is: if oppression can be systematic, can redress be as well?

Incredibly, Voyage is Lewis’s first published volume. Winning the National Book Award for a first book of poetry is virtually unheard-of, but such is the power of Lewis’ verse. The first and last sections, which bookend the title project I described above, ensure that we get to hear some of Lewis’ own voice, without the filter of found material. This is another poetic rarity — usually conceptual and lyric poetry are like oil and water, unmixed in a single volume. With the final section, Lewis accomplishes just such a feat, by seamlessly transitioning back to the personal, which seems to gather political steam from “Voyage.”

In the final section, Lewis treats child sexual abuse, generational trauma, and what is perhaps the underlying trauma of the book, mentioned in both the first and last poem: “The black side of my family/ owned slaves.“ These poems are lyrical, potent, vital, with lines like “Even/ Death contains pleasure—six feet below understanding” and “But mostly I have wondered: How/ does one name a slave Happiness?” These last pages get to the heart of why poetry is more relevant than ever: Only poetry can unearth these enormous truths and do them justice in a mere 133 pages; only Lewis could do it so brilliantly. How’s that for a concept?

Order your copy of Voyage of the Sable Venus: and Other Poems by Robin Coste Lewis from your local feminist bookstore here.