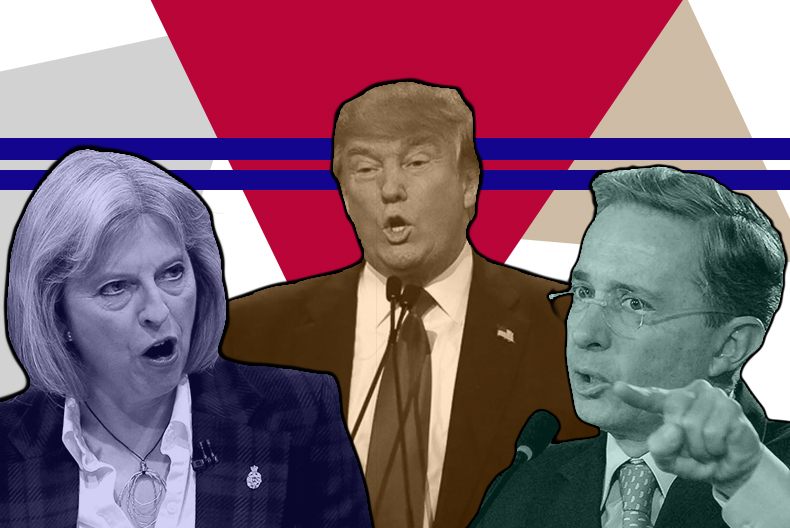

From left to right: Prime Minister Theresa May, President-elect Donald Trump, and ex-President Álvaro Uribe

THIS YEAR has been full of surprises. Many governments put important decisions in the hands of their people, and the ballots revealed the conservative nature of the majority. What does this mean for the liberals among us? Let’s look at three of the biggest examples from this year.

Widespread Xenophobia in the UK

Brexit — the term used to describe the UK’s exit from the European Union — was the cause of great debate earlier this year in its constituent countries. Pro-Brexiters touted anti-establishment viewpoints and expressed the need to prioritize the culture of Britain, and tended to be against immigration. The sentiment at the core of the pro-Brexit campaign was that Britain had lost control of its own affairs, immigration had caused a loss of national identity, and the country was being forced to accept too many refugees. Anti-Brexit advocates, known as Remainers, put more value on the economy and the consequences of leaving the European Union. Interestingly, they did not sing the praises of the European Union, instead focusing on the economic relationship between Britain and its largest foreign direct investment source. The results of the June 23 referendum, with 71.8% of the population participating, were in favor of Brexit, 52% to 48%. While no logistical plans for seceding from the EU have been formalized yet, Prime Minister Theresa May, the leader of the Conservative Party chosen to replace PM David Cameron, continues to make reduced immigration a major issue of her term in office, both nationally and as she meets with foreign officials.

Colombia’s Uncertain Political Future

In October, the Colombian people voted against a peace deal with Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC), a Marxist rebel group that has waged guerrilla war against the government since the 1960s. FARC has been funded, in part, by the drug trade and other traditionally-illegal activities, and the U.S. government has provided military aid to the Colombian government since 2000. In September 2016, Colombian President Juan Manuel Santos and FARC leader Timoleón Jiménez signed the peace agreement known as “Plan Colombia” in the presence of UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon and U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry. It involved FARC handing over its weapons in exchange for amnesty, and becoming a political party with 10 secured seats in the next two Colombian elections. Many people, including former President Alvaro Uribe, found the agreement too beneficial for FARC — valuing peace over justice — while others simply did not trust the group. While it was rejected by a popular vote referendum in October — by less than a 1% margin — a revised deal was negotiated and signed on November 24. The revised deal will not be put to popular vote again, but will be decided upon by Congress; the Democratic Centre Party, which was founded by former President Uribe, has voiced major concerns against the “cosmetic” changes to the deal, and it is expected to put up resistance to the deal as its proponents seek congressional approval.

The Rise of Fascism in the United States

When it came to the U.S. presidential elections, the entire world seemed to grind to a halt and watch with bated breath as the election cycle dominated the better part of 2016. Both candidates were reduced to caricatures, clever soundbites played one against the other. In many ways, Democrats and other liberals fought a war against themselves while trying to best the Republican Party at the same time, divided over whether to nominate Hillary Clinton or Bernie Sanders as the Left’s official candidate. The party never seemed to pick itself up and band together after that, and this may have resulted in many eligible voters staying home. While Clinton won the popular vote by over 2 million ballots, she received only 232 electoral votes to Trump’s 290 — an event not seen since Al Gore’s loss in 2000. Trump’s white supremacist rhetoric led him to the top, and the world has been left slack-jawed, wondering how the United States of America has come to this. Many people fail to realize that his win is an obvious indication of the world swinging dangerously to the right, but we have had other, less blatant, warning signs all year.

The results in all of these countries reiterate the conservative nature of the people around us, as well as their ability to show up in large numbers. In Colombia, only 38% of the electorate participated in the referendum. The U.S. saw a voter participation rate of 58%. Who is staying home? Do liberals have a false sense of security that leads them to stay home and expect their desired result? In recent events, it certainly seems that the people with something to prove are the ones to show up.

At this point, our focus needs to be on the voice of the people. Today, it seems that we are hearing from the other side, louder and more clearly. Is it that we are outnumbered? Are the pollsters doing it wrong? Or is that we are busy fighting battles within our own communities? Distracted by the Sanders vs. Clinton conversation? Over-confident in our positions? It is time to look at ourselves, and assess the ways we contribute to the dynamic we’re seeing play out all over the world.

Women are half of the world’s population, and there are 1.8 billion young people in the world. There is power in those numbers, activated when we speak up and show up. Recent history has shown that, with the help of social media, we are quick to speak with conviction. A major challenge we face is showing up, and turning those words into actions. Yes, we want peace, and we believe everyone around us wants peace, but should that make us comfortable enough to stay home instead of voting?

Another challenge is maintaining our focus on desired outcomes and shared vision, rather than allowing division because of minor disagreements. We must be able to remain committed to the greater cause, and resist the tactics of the opposing side to pull us apart by one thread. We may have preferred Sanders, but should we have allowed Clinton to lose our votes because of that, leaving us stuck with Trump? By a very small margin, Britain decided to leave the European Union — an outcome that could have been much different had there been a few more votes to remain.

One thing we know for certain is that nothing is certain. We have to take our responsibilities as citizens seriously. When we cast our votes, we do so for ourselves, for our families, our communities, and the generations that come after us. Our participation is critical to the will of the people being reflected in law and policy. We need to be on the right side of history, and failure to participate does not leave us on the line. We’re squarely on the side of everything we think is wrong with the world we live in.