I HAVE A TENDENCY to credit my neuroses for some of my finer qualities.

I never miss a deadline because I’m anxious about disappointing others. I’m very attentive to the needs of others because I worry sick about them. I’m helpful because I feel responsible for others’ well-being, and I obsess over what I can do to benefit them in some way or prevent some ill from befalling them. For me, care and responsibility for others have long gone together.

I’ve recently learned a lot about cognitive distortions, which are automatic thought patterns that skew our perspective on ourselves, others and situations we are in. When I came across the distortion called personalization — the heightened sense of personal responsibility for things and people — I saw myself immediately.

There are different ways people personalize. There’s “the perfectionist,” that person who thinks he or she personally has to do everything in order to get things done right. Then there’s “the caretaker” — the individual who feels responsible for the well-being of others to an excessive degree. I’ve realized that I’m a caretaker.

I wondered: Is it possible for me to care for others while letting go of my heightened sense of responsibility for them? What would that look like?

Around the same time I made my self-discovery, I also came across the concept of “holding space,” a particular approach toward caring for and supporting others during their times of need. This is not a term with a solid definition, and it hasn’t made its way into mainstream discourse — yet, anyway. A number of bloggers have been fleshing out the concept, though, and I’ll draw from the blogs of writer Heather Plett and artist Karen Casey Smith to highlight what I see as the more salient tenets of holding space.

It’s not about you: Holding space involves refusing to take responsibility for another’s choices or the outcomes of another’s situation. The responsibility for such things lies with the person for whom you hold space, not with you.

Trust others: This is the flip-side of the above tenet. Trust in others’ ability to choose their own way. While we may provide information and insight, we must trust the other’s ability to use those as he or she sees fit.

Know when and when not to give guidance: Holding space doesn’t demand that we keep ourselves out of the matter completely — there may be times when our personal experiences or opinions can be helpful for others to hear. But there are times when a person just needs to be heard, or when giving advice may turn into making it about you (i.e. when you’re trying to “fix” things for someone else). Don’t be afraid to ask people if they want your input or not.

Allow others to make different choices than you would: Sometimes we may feel that we’ve failed as a friend if our friend makes a different choice than we would in a given situation. Part of trusting others is understanding that they experience things differently than we do; they may have different values, or there may be other factors they are considering that we don’t understand. People are different. Don’t try to make them into you.

Holding space involves being supportive without stepping in, being present without being at the center, being open to another’s trauma, pain, or problem without trying to fix it for them. When we hold space rather than step in, we care better for others by giving them the space to be responsible for themselves. In this way, we respect them more fully as human beings with agency.

In our efforts to combat cognitive distortions like personalization, it can be helpful to consider where they may originate. One possible source is gender norms. The archetype of woman as self-sacrificial caregiver and nurturer inhibits holding space by encouraging women to make it their mission to fix things for others, to “make” them happy. Care is not strictly a female norm; men are expected to care in a different way – by providing and protecting. Men have their own gender norm to live up to: “The man with the plan,” with the power to execute said plan and the aggressiveness necessary to get what he wants, or what he wants for others. Like “the perfectionist,” men guided by this norm may question others’ agency and try to take over matters themselves. Both gender norms encourage stepping in rather than holding space.

There are times when stepping in is valid – when someone is in danger, for example, due to mental illness or substance abuse. But these are anomalous cases, and that’s what I need to get through my head. The vast majority of people are both capable and deserving of agency. We can hold space for people to share, hash out, vent, and make their own decisions. We can care without feeling responsible for others’ choices, feelings, and actions.

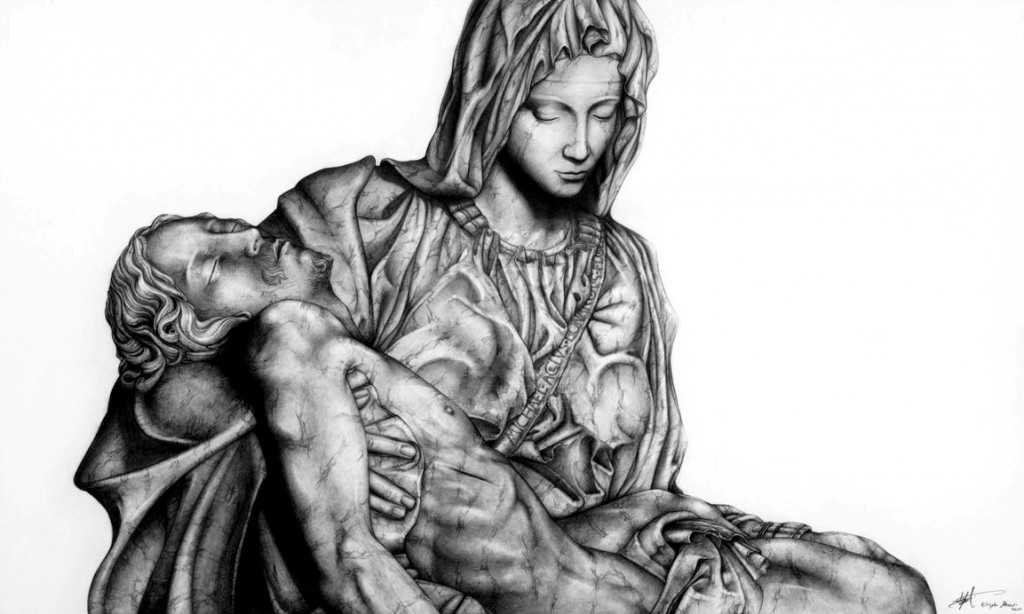

Image Credit: deviantArt/lonewolf22056