Actually, that’s how. They stoop.

Especially if “they” is the L.A. Times, relying on sensationalist headlines and clickbait tactics that were once considered, and still purported as, the journalist’s enemy. (Although city papers have always been OK wading in mucky water to catch the most fish.)

Case in current point: At the 2014 Cannes Film Festival, 46-year-old Pamela Anderson revealed to a crowd gathered for the launch of the Pamela Anderson Foundation, an organization dedicated to “human, animal and environmental rights,” that she was sexually molested, raped, and gang raped as a child. She explained that she chose the venue as an opportunity to share “events that in surviving drove [her] to this point, right now.”

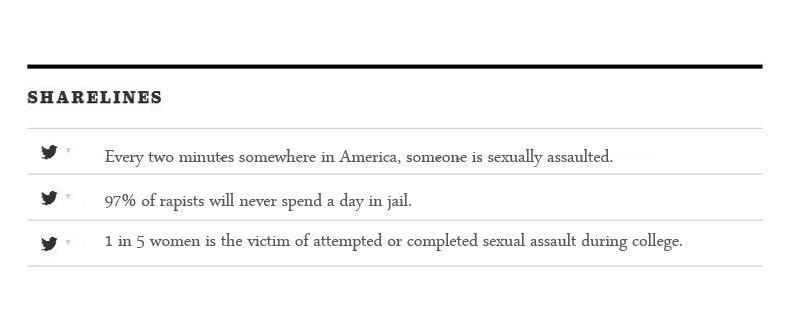

Anderson’s admission drew pertinent attention to harsh realities and the facts about rape and rape culture that remain: Every two minutes somewhere in America someone is sexually assaulted. One in six women report being victims of rape or sexual assault. 44% of rape victims are under the age of 18. 15% of rape victims are under the age of twelve. 60% of victims will never report their rape and 97% of rapists will never spend a day in jail. One in five women is the victim of an attempted or completed sexual assault during college.

But her admission also gave papers like the L.A. Times the soundbites necessary to compete with clickbait sites like BuzzFeed and Upworthy (which, yes, uses clickbait in the name of activism). The same L.A. Times, which refers itself as “principled,” “above reproach,” and claims that it does not let “the behavior of the pack set standards for us.”

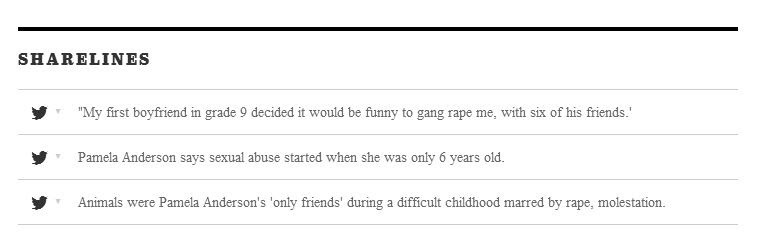

In an article posted on May 19th, “Pamela Anderson reveals childhood sexual abuse, launches charity,” the paper settled on the following pull quotes to lead in — or as they call them “SHARELINES” — to their article.

This kind of audience engagement is what the New York Times report refers to as “Audience Development” — the work of expanding a loyal and engaged audience in three steps: discovery, promotion, and connection, the last step being the way the paper develops a two-way relationship with readers, Twitter being one of the main modes of reciprocity.

“Perhaps because the path forward is not clear and requires very different skills,” the report details, “we are putting less effort into reaching readers’ digital doorsteps than we ever did in reaching their physical doorsteps.” In short, this means the Times has to go out and find their readers. Not the other way around. Which is what the L.A. Times attempted to do with these sharelines; go out and grab their readers’ attention by appealing to their worst, hungry for gossip, sensibilities. But these puerile attempts strike a nerve the way model Irina Shayk’s topless “Bring Back Our Girls” photo did, playing on the suffering of others purely for self-promotion.

The L.A. Times may argue this is distinctively journalistic– a presentation of the facts without emotion or burying the lede with dramatic overtones, a trend that plagues the mainstream media as a carry-over from satirical news programs like The Daily Show.

However, the addition of the little bird, that cultural marker that reduces Anderson’s history to a Tweet, banks solely on her celebrity to guarantee social media exposure for the paper. It’s a tactic one might expect to find on TMZ — the celebrity “news” site that blows L.A. Times readership out of the water. In March of 2014, TMZ had over 12.6 million unique visitors to their site. The L.A. Times, the fourth most read newspaper in the United States, had 9.7 million. They have to find some way to compete, right? And it’s no secret that juicy gossip headlines sell more than anything else.

It’s dense with contradictions at best, at worst, it’s “absolutely sick,” according to Beth Lalonde, author of Medium’s most read post of March, 2014, The “Divergent” Rape Scene: Here’s Why It Matters, who had the following to say:

“Those sharelines are,” she said, “intended to serve as clickbait for people more interested in the ‘salacious’ details of this celebrity’s sexual abuse, than actually ending the problem of rape.”

It’s a red herring, or multiple herrings in bird suits, that the paper seems happy to exploit.

“When I wrote my piece on Divergent‘s rape scene,” Lalonde continued, “I only included one line about my own experience of sexual assault, and purposefully made it very vague. And still I had grown men tweeting at me, asking me to explain the details of the incident because it didn’t sound, to them, that I had ‘actually’ been assaulted.”

Which is what the papers wants. Drama. To stir the pot and create a digital presence broader than their current readership.

But what if the sharelines looked like this?

These facts are no less true. They should be no less compelling. But, because Tweets are essentially headlines without the giant lettering or little boys in caps yelling in the street, papers craft them from the most scandalous part of the story — when they can. In Anderson’s case, it was easy.

Considering 80% of Millenials get their news from social networks, we have to wonder if Tweets can engage political content without feeling abrasive and/or opportunistic? There must be a way to forge mutuality — or as the New York Times calls it, “connection,” without capitulating to the enemy forces — a cavalry of bees buzzing to the tune that financial profitability trumps journalistic integrity. That’s partly what the New York Times report is about after all– how to move forward while concurrently beating the Internet at its own game. This should not be a case of “if you can’t beat ’em, join ’em.” Sensationalism has no place in journalism.

“Credibility,” reads the L.A. Times Ethics Guidelines, “a newspaper’s most precious asset, is arduously acquired and easily squandered. We live and work in a media environment suffused with hyperbole.” Would it be feasible for the newspaper to use the sharelines as an opportunity to proliferate the facts instead of the drama?

These days when it seems as if you’re either at the table or on the menu, a story like Anderson’s shouldn’t be served as the appetizer.