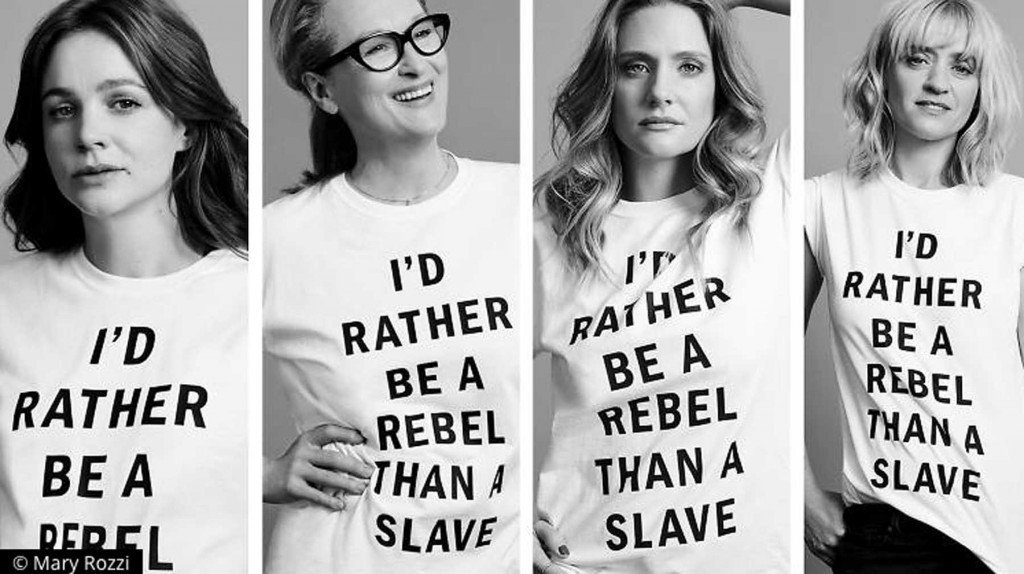

EARLIER THIS MONTH, a marketing campaign for the new film Suffragette showed the (all-white) cast — including Meryl Streep and Carey Mulligan — wearing tee shirts featuring these words: “I’d rather be a rebel than a slave.”

For context, this was a phrase that was first uttered by one of the leaders of the British movement for women’s suffrage, Emmeline Pankhurst (who will be portrayed by Streep). I have to say, I winced when I saw the images. I knew it was tone deaf, certainly, and revealed a stunning lack of awareness of the US-based liberal feminist movement and its predilections.

However, within 24 hours, a major publicity misstep had become fodder for the Twitter outrage factory, which assembled and reassembled the pieces of the problem until we were presented with a brand-new idea – the suffragettes themselves, back in the late 1800s/early 1900s, were racists, plain and simple. The iron hand of think-piece law soon decreed that, although the majority have not yet seen the movie, we must assume it to be racist and not see the movie. And those who had seen the movie (like myself) must feel terribly guilty (especially if we failed to see it was indeed racist and sound the warning bell early on).

A week or so before, I had seen the movie and then interviewed the writer, Abi Morgan. In my introductory questions, I did, in fact, pose the problem of whether this movie would play well with contemporary American audiences. The film reminded me of last year’s gay rights movie Pride in its focus on both direct action as a form of protest and on issues relating to social class divisions. As Paul Owen recently wrote in The Guardian: “Americans are acutely conscious of race, in the way British people are acutely conscious of class.” Or, more pertinently, Americans often stubbornly ignore class issues (unless they’re pitting a tiny uber-rich 1% against the rest of us, as though the rest of us were all living to the same standard – a recent, post Occupy-movement phenomenon) in favor of believing that we’re all just one more year of really hard work away from being a billionaire. This hope is surprisingly persistent, in spite of the fact that social mobility in the US is very low, meaning the rich tend to stay rich and the poor tend to stay poor.

This is important because Suffragette takes a story told usually from the perspectives of middle and upper-class women and ties it, instead, to a working class woman, Maud Watts, who has worked in an industrial laundry from childhood – hard, sometimes dangerous, physical labor for which she is paid far less than her husband who works alongside her. She is, essentially, owned by her husband and has no rights over her earnings, what they have bought, or even her own child, who, during the course of the film, is put up for adoption by her husband without her consent. She suffers sexual harassment, abuse, and rape at the hands of her boss until he finds a younger worker to focus on. If we look up the definitions of “slave,” we’ll come across these meanings: “a person who is the legal property of another and is forced to obey them” and someone who “works excessively hard without proper remuneration.” It doesn’t seem that much of a stretch that a real-life Maud Watts might call herself a slave. When she did not obey those who owned her, she lost everything.

So, were the suffragettes racist? As Spiked Online writer James Heartfield puts it – No. In an article I suggest everyone read and read again, he details how exactly those involved in the movement fought against racism at a time when “there wasn’t even a word for it.” Contemporary liberal American feminism is jarringly a-historical and anti-context. What is at the core of the response to the Suffragette marketing blunder? Heartfield suggests it is the insecurity provoked by being faced with a social justice movement that relied on what today would be deemed “terrorist” actions – that is, destroying property owned by the government and the wealthy (without harming anyone but themselves) – to make an impact, instead of hashtags.

During the post-marketing blunder debate (I hesitate to call it that as very little in the way of debate actually occurred), it was concluded that Suffragette was a “safe” movie that didn’t try to push the boundaries. A movie that opts to focus on a working-class woman over a known (middle or upper-class) leader of the movement, and shows the extent of the movement’s direct-action methodology, is not “safe.” At a time when environmental activists who destroy corporate property are thrown in maximum security jails under anti-terrorism laws, it’s not exactly “safe” to make an inspiring movie starring Meryl Streep that shows women blowing up a government official’s home. To de-radicalize the actions of the suffragette movement in retrospect in order to fit a present agenda is counter-revolutionary and thoroughly conservative. These women went on hunger strikes in prisons, were violently force-fed, left to almost die and then released, only to be put back in jail when they were strong again. In a recent profile of Gloria Steinem in The New Yorker, she reminds us to question who is served best by these conflicts played out on the internet: “You have to ask where a lot of these posts about our so-called divisions on issues like race and gender come from. What’s the context? Who’s arguing?” Who does it serve to de-radicalize the actions of the suffragette movement and persuade women not to see the movie?

Of course, it can be deeply gratifying to watch a movie in which those rebelling against an oppressive power win (whether it’s a real-life story, or a fictional one like in The Hunger Games and Divergent franchises). That gratification in itself can be counter-revolutionary, because it satisfies the emotional — “spiritual,” perhaps? — need within us without requiring us to actually do anything. However, a movie like Suffragette should be inspiring (a note tothe NSA: I am not advocating today’s feminists blow up government officials’ houses, please don’t deport me). As Gloria Steinem also said in The New Yorker profile, whatever your stance on social media, “you still have to make change happen in real life, because empathy — the ability not just to know but to feel — only happens when we are together with all five senses.” Class, unlike race, cannot be deduced from a Facebook or Twitter profile picture.

It doesn’t seem that much of a stretch that a real-life Maud Watts might call herself a slave. When she did not obey those who owned her, she lost everything.

Suffragette screenwriter Abi Morgan also wrote The Iron Lady, the biopic depicting the life and career of former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. In our interview, we discussed the irony of that fact: that the first female Prime Minister was a staunch conservative who, for all you Americans out there, was essentially a female Reagan in her politics. It should be a reminder to contemporary feminists that the end goal should not be to just see more women at the top of the ladder – as CEOs or presidents – and that an elected Hilary Clinton is a “safe” victory to pursue. For her, a working-class background is a folksy, sentimental bargaining chip in her bid for power, but it is far more important that she is now one of the economic elite, and will be one for the rest of her life.

Would the suffragettes vote for Hillary as Democratic candidate? It’s a ridiculous question, but no more ridiculous than claiming they were racists. All I know is it isn’t a betrayal of their fight to decide not to endorse Clinton and her views. The suffragettes? I reckon they’d vote for Bernie Sanders.