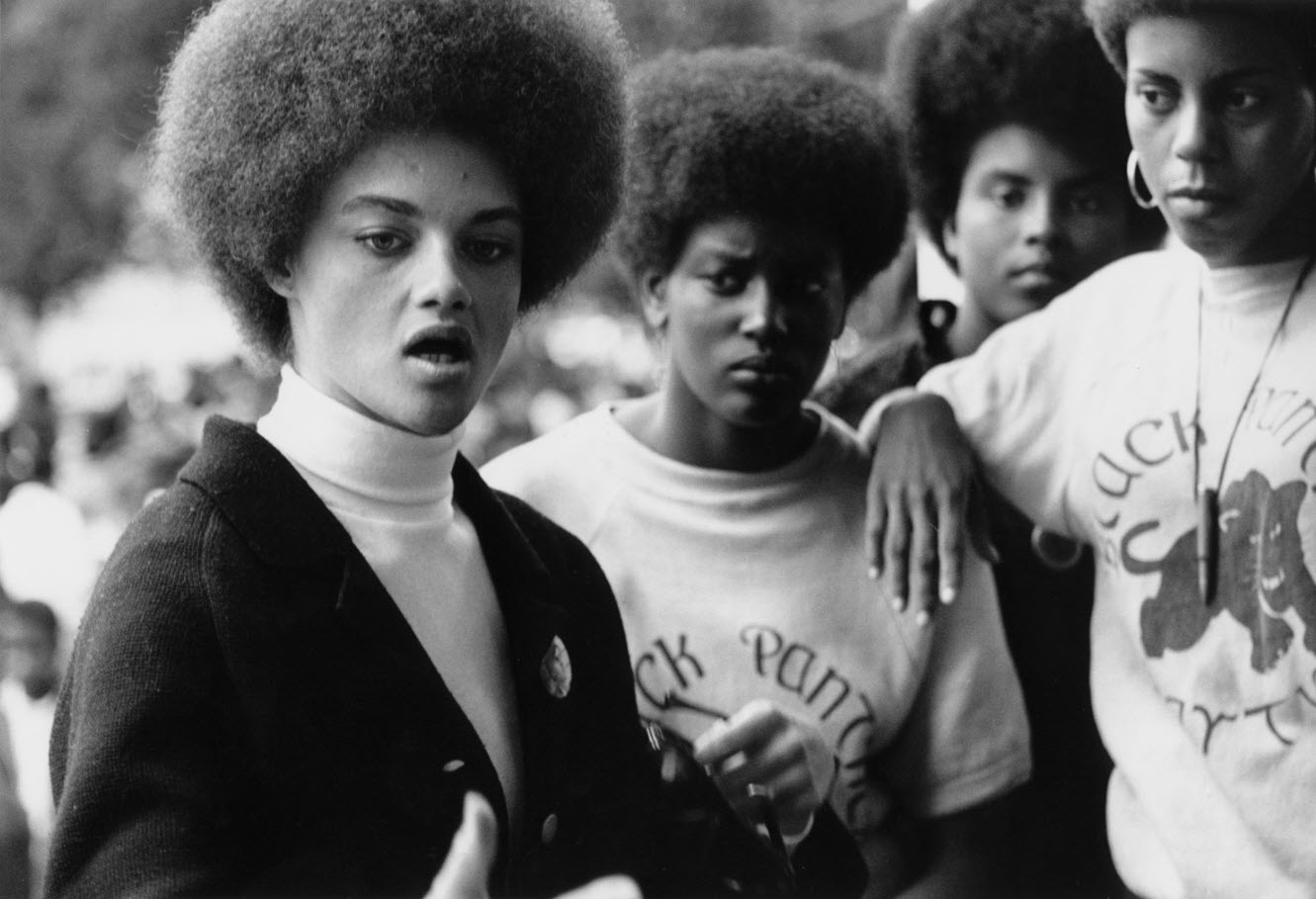

Kathleen Cleaver (l), a Black Panther Party member and a black feminist

WHILE FEMINISM IS DEFINED as the belief in political, economic, and social equality of all genders, intersectional feminism takes other identities into consideration. It recognizes the way gender, race, sexual orientation, religion, nationality, and a host of other identity markers shape our experience in and of the world. The concept is frequently theorized, but rarely put into context and practiced. Intersectional feminism does not come naturally to many people, and has to be a diligent, intentional practice. For the most marginalized communities, this is a point of contention because their lives make it impossible to view or exercise feminism in any other way. The community of black women is one that is constantly calling for more intersectional feminism while struggling with the reality of wearing two visible identities, and carrying expectations of both. It is irrefutable that black and woman are intertwined identities, not able to be divorced or dissipated.

A major concern for feminist women is gender-based violence and discrimination, a spectrum that includes sexual harassment, rape, and murder. As such, attention is often put on domestic violence and sexual assault, with everyone in agreement that these violent acts must be stopped. For a black woman, the issue can be more complex. When violent acts are perpetrated by black men, it is important to acknowledge the factors involved, intermingled with misogyny and complicated by systemic racism and oppression, “hypermasculinity,” homophobia, and stigma around and denial of mental health issues. These factors must be discussed and examined, but not used as justifications for violent acts against women. In conversations about justice, the issue of black mass incarceration and its link to the prison-industrial complex is a necessary consideration. It is not easy to raise these points as women who believe in and understand the need for gender equality, but it becomes a duty as we learn more about the conditioning, existence, and criminalization of black men and the continued fight for racial equality.

The toxicity that we know as hypermasculinity has affected melanated kindred and me for eons. Since slavery, we have been repudiated of our freedoms and civil rights, stripped of our identities… Black male hypermasculinity has been utilized as a culturally hegemonic tool, which reinforces negative stereotypes of black men across the internet, the news, magazines, and the radio. — Patrick J. Derilus

In 2015, catalyzed by a joke made by comedian Hannibal Buress, a media firestorm brought sexual assault allegations against Bill Cosby to light. More than 40 women have made reports of incidents dating as far back as 1965, and Cosby now finds himself in court fighting many criminal and civil suits. The court of public opinion, on the other hand, has reached no consensus on Cosby’s guilt. Women’s rights activists and advocates are trained and expected to believe survivors when they share their stories, and this was only bolstered by the number of accusers. For black women, however, the issue of race could not be ignored.

The black community was not able to deny the possibility that the allegations could have been part of an elaborate ploy to take down one of the most well-respected black men the U.S. In speaking about the issue, black women were frequently forced to choose between being a black person or a woman, with the assumption that a black person could not accept accusations against a black man without evidence and a woman could only assume his guilt with the accusations of more than 40 women. Add to that the infrequently raised point that white actors accused of sexual violence — like Woody Allen — have not received and do not receive the same negative media attention or backlash in the form of lost deals and networks pulling their work, and questions mount on questions. This terrain is difficult to navigate, with no right answers or positions, and no way to escape the question. Feminists are always expected to have a position, share it, and be infallible in it.

An everyday example of these dueling identities is the relationship black women have with hip hop. While the music is enjoyable and the lyrics are clever, many of the songs are deeply misogynistic. From calling women b*tches — in a derogatory way, not to be confused with reclaiming the word — to reducing them to sex objects, hip hop is damaging in the most unnecessary ways. The love-hate relationship with the genre and the talented artists is difficult to reconcile with feminism, intersectional or otherwise. A recent example is Straight Outta Compton, the 2015 biographical drama about the five young men of hip hop music group N.W.A. While it faithfully portrayed the way N.W.A. revolutionized music, the movie omitted the violence perpetrated against women. Public criticism of the movie and the failure to address the issues of misogyny and violence in lyrics and in action prompted an apology from Dr. Dre.

As gangsta rap pioneers and beneficiaries of the corporatization of rap/hip hop in the 1990s, N.W.A. played a key role in yoking rape culture and rap misogyny. Throughout their career they’ve been hailed as street poets and raw truth tellers mining the psychic space of young urban black masculinity. — Sikivu Hutchinson

In 2016, when the two presidential candidates are Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, black women are again in a precarious situation. Donald Trump is considered, by most, to be a non-option, his racism and xenophobia taking center stage every time he speaks, while Hillary Clinton appears to be the lesser of two evils. Black voters don’t know what to expect from her, especially given her history, from black mass incarceration to her influence in Haiti through the Clinton Foundation and as Secretary of State. Many women are rallying behind her, excited by the prospect of a women president, but many others cannot forget her past or the impact she has had on black lives. Still, for them, what is the alternative?

It can sometimes be difficult to fiercely embody more than one identity, and this could require confessing, like Roxane Gay, to imperfect feminism. It is not possible to be only black or to be only woman as black women. We, as feminists, carry and wear the cross of our identities — living, breathing, and embodying the intersection, expecting it to be acknowledged.